Never Look Away, the latest offering by the award-winning writer-director, Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, depicts the politicization of art in the 20th century that has lead to the marginalization of figurative and classical work.

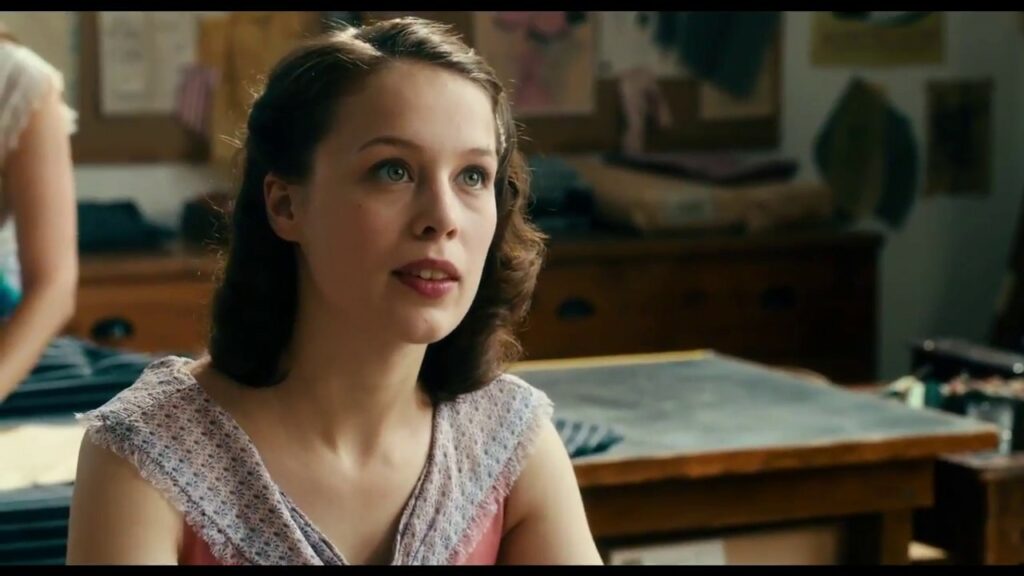

This subject, perhaps never before explored on screen, is told through the intimate and personal story of a German artist in search of his authentic voice, based loosely on the painter Gerhardt Richter.

This beautifully rendered film follows the aspiring artist over three turbulent and dynamic decades of German history, the 1930s into the ‘60s, examining how the political ideologies during this era affect one family in particular. But more importantly perhaps, the film portrays how political ideologies influence society and art. Influences that have altered the art world, changing the perception and role of art and artists, perhaps more than any other time in history.

The film opens with the beautiful, ethereal aunt taking her nephew Kurt, then a young boy with artistic aspirations, to see an exhibition of “Degenerate Art” in Dresden. Here in scene one, a Nazi gallery docent educates the visiting public on Nazi ideology, claiming to be t

It is understandable to laud such a position. The tragedy, however, is that Hitler was responsible for murdering a huge percentage of the cultural world, many talented traditional composers, artists, and musicians of this time. Was it really about the integrity of the art and the preciousness of safeguarding humanity?

This is a fascinating – albeit disturbing – example of how political leaders and machines use language that sounds noble but are fueling a nefarious agenda, quite contrary to their slogans and promises. The Nazis, as is evident in this film, who murdered the mentally and physically ill, were vicious and evil in many ways. It would be a natural response, therefore, to do and believe the opposite of what they profess. But perhaps here is a perfect example of throwing out the baby with the

After the Germans, under the Third Reich, lose the war, the Allied victors divide Germany into four zones of military occupation, Kurt (a fictionalized version of German artist Gerhard Richter, played by Tom Schilling) finds himself in art school in East Germany, under Soviet’s communist philosophy, equally rigid, restrictive, where the only acceptable form of art is ‘socialist realism’, another form of propaganda for the state.

Ironically, communism under China similarly destroyed all traditional arts, replacing divinely inspired work and classical training with art that celebrated the communist leaders, or the downtrodden worker whose only allegiance was to the government.

According to How the Specter of Communism Is Ruling Our

As Herbert Marcuse, a German socialist and a representative of the Frankfurt School wrote: “[A]rt both protests these [given social] relations, and at the same time transcends them. Thereby art subverts the dominant consciousness, the ordinary experience.” (Herbert Marcuse, The Aesthetic

Dimension: Toward a Critique of Marxist Aesthetics (Boston: Beacon Press, 1978), ix.)

When Kurt and his wife Ellie escape to the West, shortly before the wall is built, he is accepted to a prestigious modern art school in Dusseldorf. Here he must now contend with reactive, perhaps equally warped, ideas of art as he tries to discover the creative voice. Continuously mocked for painting at all, Kurt is told that ‘painting is dead’, while his fellow students are preoccupied with piles of potatoes, and slashing canvases.

Modern art prioritizes self-expression over formal technique in the name of freedom, but art students trained in most contemporary art schools today have come to discover conversely that not knowing how to draw a figure renders one not very free to express themselves whatsoever and ironically becomes a great limitation on creating art.

“Art once made a cult of beauty. Now we have a cult of ugliness instead. This has made art into an elaborate joke, one which by now has ceased to be funny”, says philosopher Roger Scruton, who teaches and lectures extensively on art and the importance of beauty in society had written, “The art establishment has turned away from the old curriculum which puts beauty and craft at the top of the agenda.”

It’s hard to imagine that art, in the tradition of DaVinci, Michelangelo, or Rembrandt, would be mocked in art schools, but art has, in fact, become so polarized and reactionary that this mentality has become prevalent in art schools around the world. It seems that the legacy of this tumultuous era has left a profound, understandable, and lamentable confusion: if Nazis are bad, and they say that classical art is good, then classical art must be bad, and modern art must be good. Donnersmarck, through Kurt, shows us that the most compelling art is transcendent. Unlike Kurt’s university teacher, who seems lost in a loop of his human experience and suffering, driven to make piles of fat, Kurt however, seems to finally transform his skills and life experience, both positive and painful ones, into beauty.

Kurt uncovers some truth he can’t explain rationally as his life, his childhood memories, losses, and strange karmic ties to both his loving birth family, as well as nefarious relations he had married into, eventually, like the sand in the oyster’s shell, produce something magnificent. Maybe it is that very divine presence that Communist driven art would denounce that lies beyond the traceable contributing factors of creativity, the enigmatic element of the process, some might call hallowed.

Leave A Reply